The Japanese Educational System

The schooling years in the Japanese

education system are segmented along the lines of 6-3-3-4: 6 years of

primary or elementary school; 3 years of middle or junior high school; 3

years of high school; and 4 years of university. However, the government has just announced (October 2005, Daily Yomiuri)

that it is intending to make changes in the Education Law to allow schools

to merge the 6-3 division between elementary and middle schools. The key purpose for this change is to allow elementary and middle schools

to pool or share their resources, with special regard to making available

specialist teachers of middle schools to elementary schools.

Many private schools, however, offer a

six year programme incorporating both junior high school and high

school. Specialised schools may offer a five year programme comprising

high school and two years of junior college. There are two options for

tertiary education: junior college (two years) and university (four

years).

A school year has three terms: summer, winter and spring, which are each

followed by a vacation period. The school year begins in April and ends

in March of the following year.

An elementary school (from 6 years) and junior high school (3 years)

education, i.e. nine years of schooling are considered compulsory (see

pages on legality of homeschooling).

This system, implemented by the School Education Law enacted in March

1947 after WWII, owes its origin to the American model 6-3-3 plus 4

years of university. Many other features of the Japanese educational

system, are however, based on European models.

Compulsory education covers elementary school and junior high school. A

break from the past, modern public schools in Japan today are mostly

co-ed(more than 99% of elementary schools). The Japanese school year

begins in April and students attend school for three terms except for

brief spring and winter breaks and a one month long summer holiday.

Some Statistics

Japan has 23,633 elementary schools, 11,134 junior high schools, 5,450

senior high schools, 995 schools for the handicapped, 702 universities,

525 junior colleges, and 14,174 kindergartens (May 2003 figures). School

attendance rate for the nine years of compulsory education is 99.98%.

About 20.7 million students (May 2003 figures) were enrolled in educational

institutions in Japan from the kindergarten to university levels.

Enrolment of the population of students may be broken up into:

1,760,442 in kindergartens;

7,226,911 in elementary schools;

3,748,319 in junior high schools;

3,809,801 in senior high schools;

250,065 in junior colleges (usually two years);

2,803,901 in universities (four years) and graduate schools;

57,875 in technical colleges;

786,135 in special training schools;

and 189,570 in other types of schools.

Japanese children enter primary school from age 6. The average class

size in suburban schools is between 35-40 students, though the national

average had dropped to 28.4 pupils per class in 1995. 70% of teachers

teach all subjects as specialist teachers are rare in elementary

schools. 23.6% of elementary school students attend juku (mostly cozy family-run juku).

Suburban schools tend to be large with student populations ranging from

around 700 to over 1,000 pupils, while remote rural schools (19% of schools)

can be single-class schools.

From age 12, children proceed to middle

schools. At this point, about 5.7% of students attend private schools.

The main reasons why parents choose such schools are high priority on

academic achievement or because they wish to take their children out of

the high school selection rat-race since such schools allow their

students direct entry into their affiliated high schools (and often into

the affiliated universities).

2005 results of a survey-questionnaire sent to schools of 6th grade parents in 2 Tokyo wards showed:

- Parents who select a private junior high school for their child tend to be parents with time and economic influence (home-makers or self-employed with one child) base their decisions and place top priority on academic achievement. The most common reason for sending their children to a private junior high school was that they wanted their children to achieve a higher level of academic achievement.

- Parents who select public junior high schools make their choice on the basis of location, incidence of bullying, and personal guidance. Among parents who selected a public school outside the school district, 45% reported that a particularly important criterion was little incidence of bullying and truancy, indicating that bullying was a crucial consideration. The most important criteria for these parents in selection were distance to school, environment and whether good friends also attended the school.

- A large percentage of parents (65.1%) tend to select the school based on hearsay.

90.8% of the parents send their children to a juku or cram school, and those whose children attended cram school four or more days a week accounted for 65.2%.

98% of 15 year-old middle-school graduates go on to high schools or private specialist institutions. A high-school diploma is a considered the minimum for the most basic jobs in Japanese societies. The rate of students who advance on to senior high schools was 97.0% in 2002.

One-fourth of students attend private high schools, a small number of which are elite academic high schools. Over 97% of high-school students attend day high schools, about three-fourths are enrolled in academic courses. Other students are enrolled in the one or other of the 93 correspondence high schools or the 342 high schools that support correspondence courses.

There are 710 universities (not counting junior colleges). Almost three-fourths of university students are enrolled at private universities. The rate of students who went on to universities and junior colleges was 44.8 %.

Special education institutions exist: 70 schools for the deaf (rougakko); 107 for the blind (mougakko); 790 for those with disabilities (yougogakko). This number is considered to be inadequate.

The National School Curriculum

The elementary school curriculum covers Japanese, social studies, mathematics, science, music, arts and handicrafts, homemaking and physical education. At this stage, much time and emphasis is given to music, fine arts and physical education.

Once-a-week moral education classes were re-introduced into the curriculum in 1959, but these classes together with the earlier emphasis on non-academic subjects are part of its "whole person" education which is seen as the main task of the elementary school system. Moral education is also seen as more effectively carried on through the school routine and daily interactions that go on during the class cleaning and school lunch activities.

The middle curriculum includes Japanese, mathematics, social studies, science, English, music, art, physical education, field trips, clubs and homeroom time. Students now receive instruction from specialist subject teachers. The pace is quick and instruction is text-book bound because teachers have to cover a lot of ground in preparation for high-school entrance examinations.

High schools adopt highly divergent high school curricula, the content may contain general or highly specialized subjects depending on the different types of high schools. To view a sample curriculum of a high school (Ikoma High School), visit the following link.

High schools may be classed into one of the following types:

- Elite academic high schools collect the creme de la creme of the student population and send the majority of its graduates to top national universities.

- Non-elite academic high schools ostensibly prepare students for less prestigious universities or junior colleges, but in reality send a large number of their students to private specialist schools (senshuugakko), which teach subjects such as book-keeping, languages and computer programming. These schools constitute mainstream high schooling.

- Vocational High Schools that offer courses in commerce, technical subjects, agriculture, homescience, nursing and fishery. Approximately 60% of their graduates enter full-time employment.

- Correspondence High Schools offers a flexible form of schooling for 1.6% of high school students usually those who missed out on high schooling for various reasons.

- Evening High School which used to offer classes to poor but ambitious students who worked while trying to remedy their educational deficiencies. But in recent times, such schools tend to be attended by little-motivated members of the lowest two percentiles in terms of academic achievement.

About School Life

School life often receives bad press on delinquency, bullying (ijime) or behavioral problems or the spate of horrendous and baffling crime knifings and killings taking place in schools in the past decade that were once unheard of in the country. Student life in public elementary schools in general is however acknowledged by most Japanese to be largely enjoyable, except for some students that can set in during the transition to junior high school.

Rigorous swotting for entrance exams is said to characterise student life in Japanese schools beginning just before entry to middle schools. To secure entry to most high schools, universities, as well as a few private junior high schools and elementary schools, applicants are required to sit entrance exams and attend interviews.

As a result, a high level of competitiveness (and stress) is often observed among students (and their mothers) during pre-high to high school years. In order to pass entrance exams to the best institutions, many students attend private afterschool study sessions (juku or gakken) that take place after regular classes in school, and/or special private preparation institutions for one to two years between high school and university (yobiko)

The Hidden Face of Japanese Education

Beyond Academics -- School Culture

Children learn early on (beginning in preschool) to maintain cooperative relationships with their peers; to follow the set school routines; and to value punctuality (from their first year in elementary school). Classroom management emphasizes student responsibility and stewardship through emphasis on daily chores such as cleaning of desks and scrubbing of classroom floors. Students are encouraged to develop strong loyalties to their social groups, e.g. to their class, their sports-day teams, their after-school circles, e.g. baseball and soccer teams. Leadership as well as subordinate roles, as well as group organization skills are learnt through assigned roles for lunchtime (kyushoku touban), class monitor or class chairperson and other such duties.

Despite the assigned leadership-subordinate roles, group activities are often conducted in a surprisingly democratic manner. Teachers usually delegate authority and responsibility to students. Small-group (han) activities often foster caring and nurturing relationships among students.

The teaching culture in Japan differs greatly from that of schools in the west. Teachers are particularly concerned about developing the holistic child and regard it as their task to focus on matters such as personal hygiene, nutrition, sleep that are not ordinarily thought of as part of the teacher's duties in the west. Students are also taught proper manners, how to speak politely and how to address adults as well as how to relate to their peers in the appropriate manner. They also learn public speaking skills through the routine class meetings as well as many school events during the school year.

Noisy and lively classrooms, the absence of teacher supervision along with the effective use of peer supervision are most often noted of elementary school classrooms. Homework workload is not overly heavy at this stage, daily portions typically comprise kanji (Chinese characters) or kokugo (Japanese language) worksheets and one or two pages of arithmetic worksheets. Various after-school hamako or club activities or remedial classes may be held by individual home-room teachers (or schools) as they see fit.

Middle-school (i.e. junior school) instruction of academic subjects shifts gear into intense, structured, fact-filled learning and routine-based school life. Small-group han are dispensed with during academic classes. Hierarchical teacher-peer and senior-to-junior relationships as well as highly organized, disciplined and hierarchical work environments such as various established student committees, are observed at middle schools.

Juku and Exam War culture

High school environment shifts the student to a lecture-centered and systematic learning mode which is alternatively lauded for its high levels of achievement in math and science and criticized for its monotony and lack of creativity during a time geared towards competitive examinations when an intensive selection process occurs.

From middle-school to high school years, students are affected more by the after-school activities and juku culture. 59.55% of middle-school students attend juku usually the large-scale cram school chains (1993 MOE survey) compared to the 23.6% figure for elementary school students. To know more about the importance of cram schools,

Peer group culture

Peer group culture or school culture is at its peak during high school years. Entrance examinations play a strong differentiating role here. High school culture tends to be distinctive and markedly different depending on the type of high school. At this stage, students become aware of the nature and ranking of high schools that influence their future, and career opportunities, and hence of the differentiation or sorting that is taking place.

An elaborate hierarchical labyrinth exists in each school district in which high schools are ranked, based on the difficulty of admission. Different high schools also have markedly different missions, preparing their students for different destinations. Consequently, different high schools develop distinctly different subcultures.

The high school rankings also correspond strongly to the relative wealth and privilege of the students. Students with more privileged backgrounds (in terms of parental occupations and income) concentrate at the higher-ranked schools while those with less privileged background congregate at lesser ranked schools.

A key feature noted of high school culture is the competitive socialization that takes place towards university entrance examinations. Since high school institutions play the role of selecting young people based on their academic achievement, identifying some for leadership positions and others for subordinate positions. The competitive nature of university entrance examination exemplifies the selective function and ultimate sorting role of Japanese high schools.

Elite High Schools offer well-prepared one-hour lecture-style text-bound classes. Such schools have few disciplinary problems and students are spirited and well-rounded or active in after-school extra-curricular activities. Vocational High School students, on the other hand, often suffer low morale problems. Disciplinary, truancy, and delinquency (smoking and vandalism) problems are common.

Perspectives on school culture

Various viewpoints exist but the main ones may be summarized as the consensus theory and the conflict theory.

The former explains the school culture as being an important aspect of fostering the relative stability, consensus and harmonious nature within Japanese society. Viewed from this perspective, societal problems tend to be addressed by attempts to create more caring environments within schools.

The latter view sees the school culture as responsible for socializing children into accepting the dominant ideology, and for legitimizing school versions of knowledge, values and worldviews, as well as the existing inequalities across society. Schools, according to this view, recognize and reward certain types of ability in children, conduct differentiation based on so-called merits and have the effect of differentiating children into leadership and subordinate positions, thus preserving inequality across generations.

Incidentally, the consensus theory tends to correspond to the interpretative viewpoint of the Ministry of Education while the conflict theory reflects that of the teachers' union and intellectuals. The interactionist approach adopts the viewpoint that it is the participants, i.e. the students, families, teachers and other significant players in schooling who interact with the school in diverse ways and shape the schooling experience and outcomes.

The Role of Modern Schooling

Modern schools are regarded as performing four key roles:

1. Transmitting cognitive knowledge;

2. Socializing and acculturating;

3. Selecting and differentiating young people;

4. Legitimating what they teach.

Modern schools perform these roles, but the emphasis placed on the different roles varies during the course of schooling and in each different segment of the educational system.

National policy is constantly shifting priorities placed on the different aspects and roles of education. Teachers do not always agree on the nationally set priorities. Interest groups constantly assert their views on where priorities should lie.

Public schools tend to be different from private ones, following the national policy guidelines more closely than private ones. Individual schools also derive differing philosophies, based on tradition and character of the body of principal and teachers running the school.

Educational goals and the quality of education in the schools of Japan as such can be diverse, with the resulting reality that schooling scene is a complex one.

Nevertheless, some similarities can be observed and generalizations made about Japanese thinking on the role of Japanese schooling.

- There is still relatively strong consensus among the Japanese that schools are the main conduit for transmitting the basic literacy and numeracy skills and core body of useful knowledge, a necessary preparation for adult society. This is role of cognitive development.

- The schooling process and interactions within the school day are considered vital for instilling particular values and desirable behavioral dispositions esteemed by Japanese society. Many socialization studies have emphasized common features of socialization in Japanese school life, namely strong group consensus and socialization by group or peer pressure.

- Schooling is regarded to be a preparation for appropriate positions in the workforce and for adult society. By and large, most Japanese believe that schooling offers an opportunity for all children to move up the social ladder if they are willing to work hard. Equal opportunity is thought to exist in Japan through its educational system. It is widely thought that selection to higher schools is based on merit and is therefore fair and that all who work hard will achieve their goals. Schooling also plays the role of selecting young people based on their academic achievement, identifying some for leadership positions and others for subordinate positions. The competitive nature of university entrance examination exemplifies the selective function of Japanese schools.

- Schools legitimate the version of knowledge imparted to students as true and neutral by teaching it. This comes to light especially in the brewing political hot potato that is the history textbook controversy.

Educational Reform & Other Current Issues

More than 90% of all students graduate from high school and 40% from university or junior college. 100 % of all students complete elementary school and Japan is repeatedly said to have achieved 100% literacy and to have the highest literacy rate in the world since the Edo period.

The Japanese educational system has been highly regarded by many countries and has been studied closely for the secrets to the success of its system, especially in the years before the economic bubble burst. However, following the bursting of the bubble and the ensuing decade of recession, a number of issues have come under scrutiny both at home and abroad. To read more about other current issues such as bullying, school refusal and youth delinquency,

Higher Education

Japan has already begun to experience a population decline, with the result that many universities are already having difficulty maintaining their student populations, although entry into top ranks of the universities remains hugely competitive. The emerging and foreseeable trend is that many universities will have to try to attract large numbers of foreigners or diversify or face closure. It is also now said that a university education in Japan is within easier reach of students today, but that the quality of that higher education is now in question despite the many educational reforms that have been set in motion.

In his book Challenges to Higher Education: University in Crisis Professor Ikuo Amano noted that the critical public is far from being satisfied with these series of reforms. The reason is that the selection process of old for entry to the so-called 'first-tier universities' remains fundamentally unchanged. That is, there has been nothing done to ameliorate the entrance war for entry into these most notoriously difficult to enter institutions that are at the nucleus of an examination based on numerous subjects. Furthermore, in a society that places more importance on 'credentialization' or labelization or branding (gakkooreki) of the name of the school from which one graduates, than on simply possessing a university education, no matter how much the selection process of the university applicants is reformed, students will continue to strive to enter a small number of 'top-tier' or 'brand-name' universities (gakureki) and the severe examination war will not disappear. In this sense, the university entrance reform is a permanent issue for Japanese universities.

Each academic year begins in April and comprises of two semesters. Basic general degrees are four-year degrees, a feature adapted from the American system. Undergraduate students receive instruction via the lecture and seminar group method. The general degree may be followed by two-year Master's degrees (generally a combination of lectures and guided research) and then a three year Doctorate (largely based on research) where these are offered.

Graduate education in Japan is underdeveloped compared to European countries and the United States with only slightly more than 7 percent of Japanese undergraduates going on to graduate school as compared to 13 percent of American undergraduates. Postgraduate educational offerings are weak and the number of universities offering postgraduate programmes or a wide variety of programmes, is small, compared to that in other industrialized western countries.

Japan has about three million students enrolled in 1,200 universities and junior colleges and consequently the second largest higher educational system in the developed world. Japan also has one of the largest systems of private higher education in the world. The 710 odd universities in Japan can be separated into 3 categories: highly competitive, mildly competitive and non-competitive (the schools that are first-tier being the infamously difficult to enter ones). Public universities are generally more prestigious than their private ones with only 25 percent of all university-bound students being admitted to public universities.

More than 65 percent of high school graduates continue their studies; of these, over 70 percent are enrolled in private colleges and universities. Only about 10 percent of private institutions receive their financial resources from public funding, with most public funds on higher education being spent on the national and local public universities. Despite the impressive statistics, Japanese universities are considered to be the weakest link in the country's educational system.

While many western writers have, time and time again, attributed the economic success of Japan to the well-educated and highly literate population of Japan, recent writings and studies tend to be far more critical, lamenting the deplorable state and quality of higher education in Japan today. Despite the famed exam rigors and competitiveness, declining standards in education and the high school student's lack of interest in studying have lately been under spotlight. Some attribute this disinterestedness to the fact that academic effort no longer assured automatic rewards with the disintegration in the formerly stable and guaranteed lifetime employment system.

Japanese students are also widely known to traditionally consider their university days to be a social playground, a reward for the hard work and having made it there, and, as many critics have recently pointed, professors demand relatively little from their students. Brian McVeigh in his book Japanese Higher Education as Myth indicts the local university system as a de facto system of employment agencies or at best a waiting room before students hit the assembly line working world.

Despite the institutional change and sweeping national reforms underway in response to these criticisms, the key problems remain unresolved: the pyramidal-structure of the university system and entrance exam wars; the centrally-controlled curriculum and lack of individuality and creativity of students as well as the lack of competitiveness in educational suppliers.

Early National Education

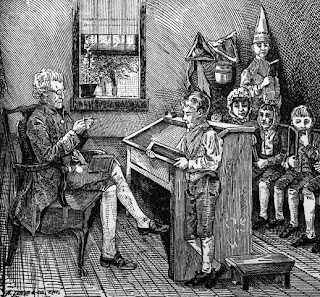

| Even in Williamsburg,

Pennsylvania in 1774, there were still few schools. Many parents

taught their children to read and write at home using a bible and a

hornbook. A hornbook was a wooden board with a handle. A lesson

sheet of the ABCs in small and capital letters, some series of syllables

and often, the Lord's Prayer, was attached to the board and was protected

by a thin layer of cow's horn. Some hornbooks of wealthy families

were very fancy, decorated with jewels and leather and included ivory

pointers. Most of them were plain and had a string around the handle

to be worn around the neck. Children wrote using a quill dipped in ink, which sometimes blotted on the page, so they sprinkled on pounce. Pounce is a powder-like sand that helps not blotch the page.

Most children wrote in a copybook because paper

was so expensive. Wealthy children had a tutor (always a man) teach them

privately. Some boys went to grammar school and sometimes even college but

never girls. Girls were given lessons on how to run a home. It wasn't even

expected for girls to spend any of their time reading! Instead their

mothers taught them how to cook, sew, preserve food, direct servants and

serve an elegant meal. Some girls were sent to teachers to learn how to

sing, play a musical instrument, sew fancy stitchery, to serve tea

properly by learning manners and how to carry on a polite conversation.

When boys grew older, they could become apprentices to learning to become

shopkeepers or craftsmen by working with and watching an adult.

Education was becoming more secular in order to produce socially

responsible citizens.

|

|

The sons of a planter typically would be taught the basics at home. The boys’ school day started around 7 a.m. in the school room with their male tutor. They had several breaks during the day. Around 9 a.m. they had breakfast, and dinner was served from 2 p.m. to 5 p.m. The boys studied higher math, Greek, Latin, science, celestial navigation (navigating ships by the stars), geography, history, fencing, social etiquette, and plantation management. At this point, the sons of wealthy planters often were sent to boarding schools in England for a higher education. They sometimes stayed over in England to study law or medicine. Otherwise, they would return home to help their fathers run the plantation. The school days for girls were somewhat different. Girls learned enough reading, writing, and arithmetic to read their Bibles and be able to record household expenses. They were taught by a governess, who was usually from England and somewhat educated. They studied art, music, French, social etiquette, needlework, spinning, weaving, cooking, and nursing. The girls did not have the opportunity to go to England for higher education because this was not considered important for them. |

Bahaya Rokok bagi kesehatan

Hidup sehat sebenarnya gampang dan murah,akan tetapi kadang menjadi sebuah hal yang mahal jika kita tak mau menjaganya. Dan ketika kita sakit, barulah kita sadar akan pentingnya kesehatan. Begitu juga dengan kebiasaan merokok kita sehari-hari. Kita aka merasa rugi jika kita sudah merasakan akibat dari merokok. Bahaya Rokok bagi kesehatan akan terasa jika kita sudah terlalu lama merokok. Aapa saja bahaya merokok?Menurut penelitian seseorang yang menghisap rokok setiap hari dapat meningkatkan resiko terkena kanker laring, paru-paru, kerongkongan, rongga mulut, gangguan pembuluh darah, gangguan kehamilan dan sakit jantung. Menurut riset seseorang yang secara rutin merokok 3 hingga 4 batang sehari, delapan kali lebih beresiko terkena kanker mulut jika dibandingkan orang yang tidak merokok. Bahkan hasil terbaru menunjukkan bahwa dalam perkembangannya merokok akan mengakibatkan kanker pankreas.

Setiap tahun frekuensi penderita penyakit kronis akibat rokok semakin meningkat. Meskipun banyak riset dan bukti otentik bahwa merokok ibarat bom waktu yang bisa merusak kesehatan. Ini dikarenakan rokok memunculkan rasa kecanduan. Di dalam rokok terkandung sebuah zat yang bernama nikotin. Zat ini bisa menimbulkan efek santai dan inilah yang membuat kebiasaan merokok sulit untuk ditinggalkan.

- Asap Rokok mengandung 40 bahan kimia penyebab kanker, dan penyakit lainnya.

- Ketika merokok,beberapa bahan kimia akan menjelajah ke organ vital tubuh .

- Asap rokok juga mengandung Karbon Monoksida yang jika dihirup akan menggantikan fungsi Oksigen di sel – sel darah dan mengambil zat makanan dari jantung, otak, dan organ tubuh lain.

- Di dalam rokok terdapat Nikotin. Nikotin ngerangsang zat kimia di otak yang mengakibatkan kecanduan. Zat kimia ini merangsang kelenjar adrenalin untuk memproduksi hormon yang mengganggu jantung akibat tekanan darah dan denyut jantung meningkat.

Cara berhenti merokok

Banyak cara agar kita bisa berhenti merokok. Tahapan pertama dan terpenting adalah niat yang besar serta sungguh-sungguh ingin berhenti merokok. Tanpa niat yang besar mustahil seseorang bisa berhenti merokok. Banyak mengaku diri perokok berat dan mengakui bahwa tekad mereka sangat besar untuk berhenti merokok. Namun ketika mereka keluar dan berkumpul kembali dengan teman-temannya yang merokok, keinginan itu muncul kembali. Inilah kenapa niat dan tekad itu yang paling penting ketika Anda ingin benar-benar berhenti merokok.2. Belajar membenci rokok

3. Bergaullah dengan orang yang tidak merokok

4. Sering-sering pergi ke tempat yang ruangannya ber-AC

5. Pindahkan semua barang-barang yang berhubungan dengan rokok.

6. Jika ingin merokok, tundalah 10 menit lagi.

7. Beritau teman dan orang terdekat kalau kita ingin berhenti merokok.

8. Kurangi jumplah merokok sedikit demi sedikit.

9. Hilangkan kebiasaan Bengong atau menunggu.

10. Sering-seringlah pergi ke rumah sakit, agar tau pentingnya kesehatan.

11. Cari pengganti rokok, misalnya permen atau gula.

12. Coba dan coba lagi jika masih gagal.

Archives

Contributors

- Unknown